Heine–Borel theorem

In the topology of metric spaces the Heine–Borel theorem, named after Eduard Heine and Émile Borel, states:

For a subset S of Euclidean space Rn, the following two statements are equivalent:

- S is closed and bounded

- every open cover of S has a finite subcover, that is, S is compact.

In the context of real analysis, the former property is sometimes used as the defining property of compactness. However, the two definitions cease to be equivalent when we consider subsets of more general metric spaces and in this generality only the latter property is used to define compactness. In fact, the Heine–Borel theorem for arbitrary metric spaces reads:

- A subset of a metric space is compact if and only if it is complete and totally bounded.

Contents |

History and motivation

The history of what today is called the Heine–Borel theorem starts in the 19th century, with the search for solid foundations of real analysis. Central to the theory was the concept of uniform continuity and the theorem stating that every continuous function on a closed interval is uniformly continuous. Dirichlet was the first to prove this and implicitly he used the existence of a finite subcover of a given open cover of a closed interval in his proof. He used this proof in his 1862 lectures, which were published only in 1904. Later Eduard Heine, Karl Weierstrass and Salvatore Pincherle used similar techniques. Émile Borel in 1895 was the first to state and prove a form of what is now called the Heine–Borel theorem. His formulation was restricted to countable covers. Pierre Cousin (1895), Lebesgue (1898) and Schoenflies (1900) generalized it to arbitrary covers.[1]

Proof

If a set is compact, then it must be closed.

Let S be a subset of Rn. Observe first the following: if a is a limit point of S, then any finite collection C of open sets, such that each open set U ∈ C is disjoint from some neighborhood VU of a, fails to be a cover of S. Indeed, the intersection of the finite family of sets VU is a neighborhood W of a in Rn. Since a is a limit point of S, W must contain a point x in S. This x ∈ S is not covered by the family C, because every U in C is disjoint from VU and hence disjoint from W, which contains x.

If S is compact but not closed, then it has an accumulation point a not in S. Consider a collection C ′ consisting of an open neighborhood N(x) for each x ∈ S, chosen small enough to not intersect some neighborhood Vx of a. Then C ′ is an open cover of S, but any finite subcollection of C ′ has the form of C discussed previously, and thus cannot be an open subcover of S. This contradicts the compactness of S. Hence, every accumulation point of S is in S, so S is closed.

The proof above applies with almost no change to showing that any compact subset S of a Hausdorff topological space X is closed in X.

If a set is compact, then it is bounded.

Consider the open balls centered upon a common point, with any radius. This can cover any set, because all points in the set are some distance away from that point. Any finite subcover of this cover must be bounded, because all balls in the subcover are contained in the largest open ball within that subcover. Therefore, any set covered by this subcover must also be bounded.

A closed subset of a compact set is compact.

Let K be a closed subset of a compact set T in Rn and let CK be an open cover of K. Then U = Rn \ K is an open set and

is an open cover of T. Since T is compact, then CT has a finite subcover  that also covers the smaller set K. Since U does not contain any point of K, the set K is already covered by

that also covers the smaller set K. Since U does not contain any point of K, the set K is already covered by  that is a finite subcollection of the original collection CK. It is thus possible to extract from any open cover CK of K a finite subcover.

that is a finite subcollection of the original collection CK. It is thus possible to extract from any open cover CK of K a finite subcover.

If a set is closed and bounded, then it is compact.

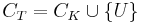

If a set S in Rn is bounded, then it can be enclosed within an n-box

where a > 0. By the property above, it is enough to show that T0 is compact.

Assume, by way of contradiction, that T0 is not compact. Then there exists an infinite open cover C of T0 that does not admit any finite subcover. Through bisection of each of the sides of T0, the box T0 can be broken up into 2n sub n-boxes, each of which has diameter equal to half the diameter of T0. Then at least one of the 2n sections of T0 must require an infinite subcover of C, otherwise C itself would have a finite subcover, by uniting together the finite covers of the sections. Call this section T1.

Likewise, the sides of T1 can be bisected, yielding 2n sections of T1, at least one of which must require an infinite subcover of C. Continuing in like manner yields a decreasing sequence of nested n-boxes:

where the side length of Tk is (2 a) / 2k, which tends to 0 as k tends to infinity. Then, by Cantor's intersection theorem, the infinite intersection

is not empty, but instead contains some point p ∈ T0. Since C covers T0, then it has some member U ∈ C such that p ∈ U. Since U is open, there is an n-ball B(p) ⊆ U. For large enough k, one has Tk ⊆ B(p) ⊆ U, but then the infinite number of members of C needed to cover Tk can be replaced by just one: U, a contradiction.

Thus, T0 is compact. Since S is closed and a subset of the compact set T0, then S is also compact (see above).

Generalizations

The theorem does not hold as stated for general metric spaces. A metric space (or topological vector space) is said to have the Heine–Borel property if every closed and bounded subset is compact. Many metric spaces fail to have the Heine–Borel property. For instance, the metric space of rational numbers (or indeed any incomplete metric space) fails to have the Heine–Borel property. Complete metric spaces may also fail to have the property. For instance, no infinite-dimensional Banach space has the Heine–Borel property.

The theorem can be generalized to arbitrary metric spaces by strengthening the conditions required for compactness:

- A subset of a metric space is compact if and only if it is complete and totally bounded.

This generalisation also applies to topological vector spaces and, more generally, to uniform spaces.

Here is a sketch of the " "-part of the proof, in the context of a general metric space, according to Jean Dieudonné:

"-part of the proof, in the context of a general metric space, according to Jean Dieudonné:

- It is obvious that any compact set E is totally bounded.

- Let (xn) be an arbitrary Cauchy sequence in E; let Fn be the closure of the set { xk : k ≥ n } in E and Un := E − Fn. If the intersection of all Fn were empty, (Un) would be an open cover of E, hence there would be a finite subcover (Unk) of E, hence the intersection of the Fnk would be empty; this implies that Fn is empty for all n larger than any of the nk, which is a contradiction. Hence, the intersection of all Fn is not empty, and any point in this intersection is an accumulation point of the sequence (xn).

- Any accumulation point of a Cauchy sequence is a limit point (xn); hence any Cauchy sequence in E converges in E, in other words: E is complete.

A proof of the " "-part can be sketched as follows:

"-part can be sketched as follows:

- If E were not compact, there would exist a cover (Ul)l of E having no finite subcover of E. Use the total boundedness of E to define inductively a sequence of balls (Bn) in E with

- the radius of Bn is 2−n;

- there is no finite subcover (Ul∩Bn)l of Bn;

- Bn+1 ∩ Bn is not empty.

- Let xn be the center point of Bn and let yn be any point in Bn+1 ∩ Bn; hence we have d(xn+1, xn) ≤ d(xn+1, yn) + d(yn, xn) ≤ 2−n−1 + 2−n ≤ 2−n+1. It follows for n ≤ p < q: d(xp, xq) ≤ d(xp, xp+1) + ... + d(xq−1, xq) ≤ 2−p+1 + ... + 2−q+2 ≤ 2−n+2. Therefore, (xn) is a Cauchy sequence in E, converging to some limit point a in E, because E is complete.

- Let

be an index such that

be an index such that  contains a; since (xn) converges to a and

contains a; since (xn) converges to a and  is open, there is a large n such that the ball Bn is a subset of

is open, there is a large n such that the ball Bn is a subset of  –v in contradiction to the construction of Bn.

–v in contradiction to the construction of Bn.

The proof of the " " part easily generalises to arbitrary uniform spaces, but the proof of the "

" part easily generalises to arbitrary uniform spaces, but the proof of the " " part is more complicated and is equivalent to the ultrafilter principle,[2] a weaker form of the Axiom of Choice. (Already, in general metric spaces, the "

" part is more complicated and is equivalent to the ultrafilter principle,[2] a weaker form of the Axiom of Choice. (Already, in general metric spaces, the " " direction requires the Axiom of dependent choice.)

" direction requires the Axiom of dependent choice.)

See also

Notes

- ^ Sundström, Manya Raman (2010). "A pedagogical history of compactness". arXiv:1006.4131v1 [math.HO].

- ^ Eric Schechter (1997). Handbook of Analysis and Its Foundations. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-622760-8. UF24, p. 506.

References

- P. Dugac (1989). "Sur la correspondance de Borel et le théorème de Dirichlet–Heine–Weierstrass–Borel–Schoenflies–Lebesgue". Arch. Internat. Hist. Sci. 39: 69–110.

- proof of Heine-Borel theorem on PlanetMath

External links

- Ivan Kenig, Dr. Prof. Hans-Christian Graf v. Botthmer, Dmitrij Tiessen, Andreas Timm, Viktor Wittman (2004) (avi • mp4 • mov • swf • streamed video). The Heine–Borel Theorem. Hannover: Leibniz Universität. http://www.math.uni-sb.de/ag/schreyer/oliver/calendar.algebraicsurface.net/calendar.php?mode=youTube&day=07.

![T_0 = [-a, a]^n](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0f0e2bce8c4ec9dcb5c449d2908a95cf.png)